- Flywheel Insights

- Posts

- How To Work: The Operating System to Beat Procrastination

How To Work: The Operating System to Beat Procrastination

Why Write About How To Do Good Work?

Many people feel distracted, overwhelmed, and behind in getting good work done.

I’m one of them.

I have a long list of things I want to do. But I rarely feel like I am consistently on top of things.

I used to wonder why it was so hard to consistently and reliably produce good work (without the ups and downs in performance).

For the longest time, I looked for hacks, routines, and tricks to defeat procrastination and to improve productivity. Although I’ve become better at work (i.e., producing more and better quality work per unit of time), I still have a long way to go.

I’m writing this post primarily for myself.

It is a collection of my thoughts and research around 1) what stops people from doing good work, and 2) what I need to do to work better.

Defeating procrastination, being effective, and producing your best work is a matter of discipline, self-knowledge, and creating the right systems. It has little to do with intelligence and willpower.

I’ll break down this post into two sections.

First, I’ll lay out the blockers that stop me and many others from doing good work. The main blocker is the human mind itself. The mind is a limited, state-dependent system that easily gets overwhelmed and seeks ways to avoid doing work.

Second, I’ll discuss the ways to deal with these blockers. These solutions attempt to create systems to improve mental effectiveness.

Part 1: The Things That Block You From Doing Good Work

1. Focusing on Being Efficient, and Not Effective

“Efficiency is concerned with doing things right. Effectiveness is doing the right things.”

“Activity is not output.”

The biggest blocker to producing good work is focusing on efficiency rather than effectiveness.

In studying the most successful people, I’ve found that much of their success stems from their effectiveness.

You can be efficient at something that doesn’t matter and does not bring you closer to your goal. Being efficient just means you are producing a lot per unit of time. Being effective is about doing the things that have the greatest impact on achieving your goals.

Most people do a lot of work that doesn’t get them closer to their goals. They put in 110% effort on tasks that barely move the needle.

There are others who do not seem to do nearly as much work but make significant progress in short periods of time.

One focuses on efficiency; the other, on effectiveness.

2. Wasting Limited Attention

Attention is finite and can get depleted with every thought and decision.

Once attention levels drop, the will to work and think goes down. Common things that tax the brain’s attention are:

Open Loops: These are thoughts or tasks that are undecided or unfinished. It’s a lack of closure that the brain experiences. It results in a constant low-level attention drain that happens in the background of your mind. Your subconscious doesn't stop thinking about unfinished things.

Context Switching: This involves regularly switching tasks. It even includes switching between (and searching for) different tabs, applications, and documents. When you switch, the brain pays a reorientation tax. This happens each time it moves from one task to another. For each task you do, the brain has to remember what it was doing, why it's important, and how to proceed.

Research by Meyer, Evans, and Rubinstein indicates that task-switching (commonly mistaken for multitasking) can consume up to 40% of an individual's productive time.

Even brief mental blocks (or "switching costs") that occur while shifting focus between tasks disrupt cognitive processing, leading to increased errors, reduced speed, and significant declines in overall productivity.

Even brief mental blocks (or "switching costs") that occur while shifting focus between tasks disrupt cognitive processing, leading to increased errors, reduced speed, and significant declines in overall productivity.

Open loops and context switching lead to a lack of focus, procrastination, and reduced capacity for deep thinking.

3. Fighting Biology

The brain is a state-dependent system. It is highly sensitive to its environment and how you feel. Fatigue, stress, hunger, and sleep dramatically distort judgment. When tired or overstimulated, the brain shifts toward avoidance and impulsivity.

The brain is also wired to optimize for different types of tasks at different times. These energy-time patterns can vary from person to person. Generally, most people experience a similar natural energy rhythm (and resist it).

Mornings: The brain has a high capacity for clear thinking and deep attention.

Midday: The brain sees a slump in mental capacity, but higher social energy. Early monks called the midday slump the “noonday demon”. This refers to a mental state of boredom and agitation that pulled them away from prayer, meditation, and meaningful work. This phenomenon is not new.

Late Evenings: Typically good for deep thinking, reading, and reflection.

It’s not a coincidence that images for ‘focus music’ involve people studying in quiet places outside of work hours. Ironically, that is when the brain does its best work.

Today, most people start their days by checking emails, ticking off their to-do lists, and attending meetings. They try to get deep work done in the afternoons between other calls, meetings, and ad-hoc interruptions.

4. Believing Your Brain

The brain is easily hijacked by novelty and shallow stimuli.

Left to its instincts, it will seek what is new, easy, and immediately rewarding.

This is why inboxes, notifications, and doomscrolling pull attention so effectively.

Cal Newport (author) argues that attention must be protected from instinct and not guided by it.

Andrew Huberman (neuroscientist) explains that feelings of resistance are physiological signals, not instructions.

This means you need to treat how you feel about a task as a diagnosis of the problem. You should not necessarily listen to what the brain recommends.

If your brain goes through this type of resistance, don't believe it.

It will result in procrastination, underperformance, and avoiding working on the important things.

This tendency is what psychologists call the cognitive miser theory.

The brain is wired to conserve mental energy. It prefers tasks that are familiar, low-effort, and quickly solvable.

Busywork fits this perfectly.

Busywork feels productive because it minimizes cognitive strain while delivering fast feedback.

Deep work, by contrast, demands slow, effortful thinking, and the brain resists it.

5. Not Knowing The Different Types of Schedules

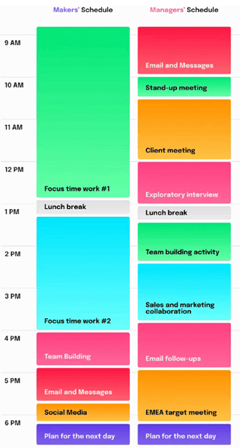

Paul Graham wrote a blog post called ‘Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule.’

In it, he describes the two modes of work that are very different from each other: Maker mode and manager mode.

Manager mode involves frequent context switching and mental stimulation.

It often involves back-to-back meetings and working on many different ‘little’ things.

It is often necessary for managers to operate in this way. Managers need to move things forward in organizations with many stakeholders, which requires extensive coordination.

Maker mode involves deep work.

This includes long, uninterrupted hours of focused work on a specific task. The output of this work can often be in the form of content (authoring a book, coding an application, writing a musical masterpiece, etc.).

The brain needs to be relaxed and have the comfort of knowing that it will not be interrupted for several hours. This allows the brain to enter a state of flow, encouraging creative thinking, in which all areas of the mind are focused on a single task.

If you are trying to get deep work done, context switching is the enemy of productivity.

The big issue here is that people often try to fit deep work sessions in between busywork sessions, which doesn’t work.

Part 2: Activities To Deal With Things That Block Good Work

There are a handful of things that you can do to fight the mental blockers that stop good work.

They involve:

Creating clarity in objectives, because the mind doesn’t like complexity

Building a schedule that follows the brain and body’s natural energy rhythms

Establishing small habits that reduce distractions and facilitates good work

Staying reminded about the goals, habits, and activities that will keep you on track.

Note: These solutions are not a one-size-fits-all.

You must be clear on what your goals are and what your energy patterns look like.

You have to balance your goals and work preferences with the demands of your specific workplace and personal circumstances.

Figuring all this out requires a good amount of detail.

It is crucial that you clearly write down your goals and constraints to figure out what works for you.

I can only give you high-level ideas to consider, not a tailored plan. Only you have the information to build a system that works for you.

To do this, I suggest you use Kidlin’s Law to determine your preferences, constraints, and ideal solutions.

“If you can write down a problem clearly and specifically, you’ve already solved half of it.”

Kidlin’s Law says that clarity creates progress.

Most problems feel hard not because they’re complex, but because they’re vague. The act of writing a problem down forces you to:

Define what the problem actually is (not just how it feels)

Break it into components.

Expose assumptions and unknowns.

That process alone often reveals the solution, or at least the next obvious step.

1. Long-Term Calendar

Most people are stuck in their day-to-day because they are unclear about what their ultimate goals are. This is not just related to professional objectives. It is a way of being more deliberate with how you approach life.

Long-term thinking is the practice of expanding your time horizon beyond the default short-term frame of days, weeks, and quarters. It involves making decisions using decades-long reference points. In practice, successful people use long-term calendars to:

Define a life-long mission (north star)

Set decade-scale direction

Make short-term plans that build toward that direction

Avoid being trapped by urgency and noise

Serial entrepreneur Jesse Itzler plans his year using the Big A## Calendar.

The way forward here is to:

1) Describe your goals: State what you want out of life within its various dimensions (spiritual, professional, health, relationships, etc.)

2) Map your goals across different calendars: Break down your goals into milestones and the inputs that are needed at various points in time.

I suggest 25, 10, and 1 years.

Doing this creates clarity and intentionality in your life.

It helps you understand why you are doing things.

It also helps you determine whether you are being effective (i.e., are you focusing on the few things that drive the most results).

2. Focus (Say No To Things You Want To Do)

“Every time we say yes to a request, we are also saying no to anything else we might accomplish with the time.”

Focus is probably THE number one productivity secret.

It's something I have struggled with, and it's easier said than done.

Focus is about deciding what not to do, even if it seems like a good idea.

Time and attention are finite. When they’re spread thin, nothing meaningful gets enough depth to matter.

This is why being ‘busy’ feels productive but rarely is. You can be extremely efficient at the wrong things.

Most people respond to this problem in the wrong way. They try to power through with brute force, coffee, and motivation.

This is what James Clear describes as increasing productive force.

It involves trying to overpower distraction and overload using willpower.

It works briefly. It’s not sustainable, and when it breaks, burnout follows.

The better option is not to push harder, but to remove resistance.

Instead of adding force, eliminate the opposing forces (distractions).

Say ‘no’ more often and reduce commitments.

This goes back to the whole question of whether you are being effective.

The reality is, you only need to do a few things well to make progress.

When distractions are removed, productivity increases, and things move forward naturally.

Focus is subtraction.

It’s choosing fewer priorities, projects, and meetings.

It’s protecting space for the work that actually matters, even when there are many good, interesting, and tempting alternatives.

There is a great quote by the legendary Apple designer Jony Ive on what he learned from Steve Jobs on Focus:

“Steve was the most remarkably focused person I've ever met in my life.

You can achieve so much when you are truly focused.

And one of the things that Steve would say [is]: “How many things have you said no to?” …and so I say: “Oh, I said no to this, and no to that…”

But he knew that I wasn't vaguely interested in doing those things anyway. So there was no real sacrifice.

What Focus means… is saying NO to something that—with every bone in your body—you think is a phenomenal idea.

And you wake up thinking about it… but you say NO to it because you're focusing on something else.”

There's another story about focus involving Warren Buffett that comes to mind.

Buffett was once asked how one should go about accomplishing their goals. He then told this person to list the 25 things they wanted to accomplish, then circle the top five. Buffett then gave his advice: avoid the other 20 at all costs.

Avoiding things can be more powerful than doing more. What do you have on your calendar or to-do list that shouldn’t be there?

3. Create a Parking-Lot System (Busywork Brain-Dump)

Regardless of how small a task or thought is, it will take up space in your head.

This requires processing power, which creates ‘cognitive load’.

It impacts your thinking and energy levels.

Your brain needs to unload this burden so it doesn’t have to rely on background memory.

Writing tasks and thoughts down will give your brain the reassurance that you will get to them later.

You will get psychological closure because you know you will work on it when the time comes.

The most important thing to do here is to literally dump your ideas and to-dos onto a piece of paper.

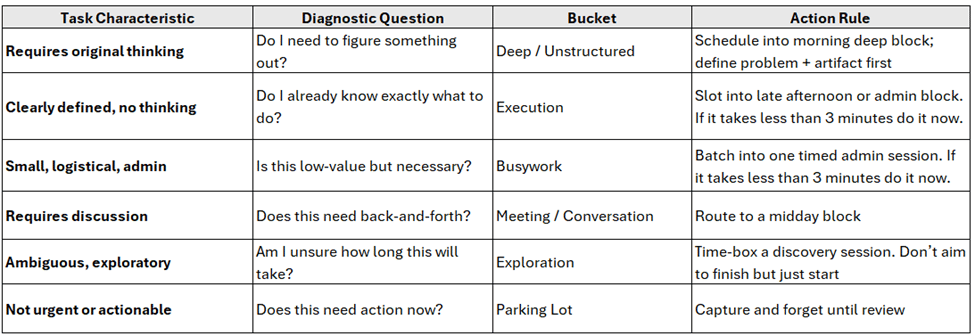

Once you have time to breathe and start planning your work, you should categorize each item on your to-do list appropriately.

1. Batch your tasks into different buckets based on the type of work required.

Maker Schedule Bucket: For thinking, creating, and exploring.

Manager Schedule Bucket: For busywork like meetings, networking events, calls, sending emails, and completing a series of short tasks.

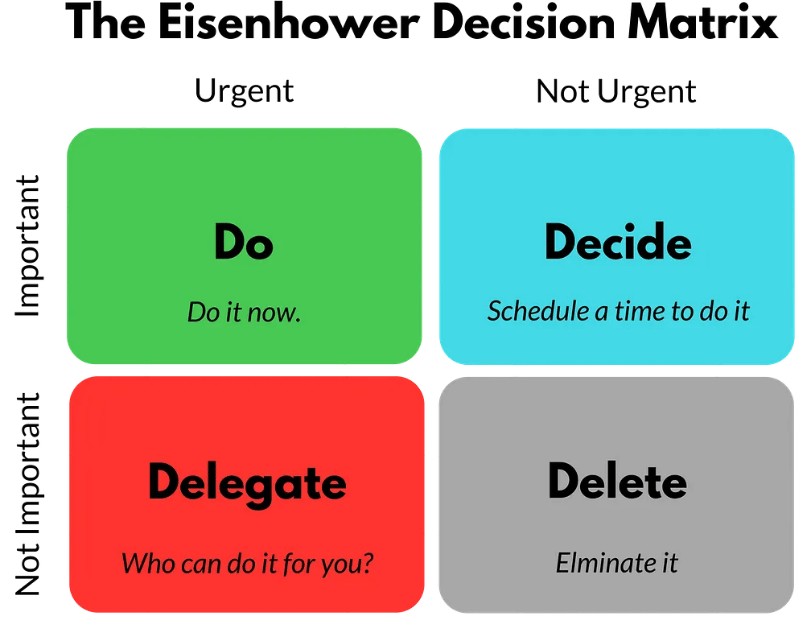

2. You should then prioritize those items based on how important and urgent they are.

Prioritize the important things. Using the Eisenhower Matrix is useful in deciding with how to move forward.

The Eisenhower Matrix is a productivity and time-management tool designed to help you prioritize tasks by categorizing them according to their urgency and importance.

4. Design Your Schedule Based on Your Energy and Type of Work

Your focus level changes throughout the day.

The work you do should align with your energy.

Most people are unintentional about when to take meetings or when they should schedule deep work.

You can determine how to label the work based on what type of thinking is required.

There are two systems of thinking, one is fast, and the other is slow.

Fast thinking (System 1) is reactive, automatic, and emotion-driven.

Slow thinking (System 2) is deliberate, analytical, and effortful. Switching between the two overwhelms the brain and degrades performance.

Having two schedules for the two types of thinking solves this problem.

Fast thinking (System 1) ➜ Manager Schedule.

Slow thinking (System 2) ➜ Maker Schedule.

Manager works tolerates taking meetings, having back-to-back appointments, and performing multiple small tasks sequentially.

Maker work needs long, uninterrupted blocks, typically early in the mornings or late at night.

Middle management in large organizations doesn’t often carve out maker time. They’re on the manager's schedule almost 100% of the time. Because of that, they will schedule meetings based on when they are free, regardless of whether you are doing deep work or not. For a manager, an empty slot on the calendar is time wasted.

Building the right schedule is harder for individual contributors (developers, writers, analysts, associates) who need hybrid calendars. They will need to find the right time to do deep work and adjust to their manager's expectations.

Early-stage founders who need to wear multiple hats have to fit both schedules into a single day.

Paul Graham describes this phenomenon well:

“When we were working on our own startup, back in the 90s, I evolved another trick for partitioning the day. I used to program from dinner till about 3 am every day, because at night no one could interrupt me. Then I'd sleep till about 11 am, and come in and work until dinner on what I called "business stuff." I never thought of it in these terms, but in effect I had two workdays each day, one on the manager's schedule and one on the maker's”

The prescription here is to time-block accordingly.

Carve out 3-4+ hours for deep work during a time when you know you won’t be interrupted.

Schedule your meetings and busywork tasks around the time when everyone wants your attention, and when your energy requires social interaction, food, and movement.

Illustration of a maker and manager’s schedules.

Don’t let urgency override energy.

A lot of what seems “urgent” isn’t usually important.

It’s just you believing your brain and avoiding the deep and meaningful work. You can delay busywork to the next available manager block in your schedule.

5. Use Systems to Beat Procrastination, Stay On Track, and Get Things Done

“You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.”

Creating the environment and systems that encourage productivity is more important than relying on effort.

Most people struggle because their work is underspecified, their environment is hostile to focus, and their days are left to chance.

Systems exist to solve this.

They remove ambiguity, reduce cognitive load, and make progress predictable.

A good system makes work predictable and approachable. When you know what to do, when to do it, and how to start, resistance drops and execution follows naturally.

Table 1: Rule of thumbs for how to categorize tasks

1) Measure What Matters

“What gets measured gets managed.”

Measurement is not about control. It is about attention.

What gets measured is what you take seriously.

The mistake most people make is to track outcomes.

Outcomes are lagging indicators and can be influenced by many external factors beyond your direct control.

What works better is to track the relevant inputs.

These are the leading indicators that tell you whether you are doing enough of the work that causes the results.

Measuring leading indicators makes things improvable.

When you do this, you can see the relationship between inputs and outputs.

You can benchmark to see how you compare to others, which will help you get better.

To make this practical, it helps to break work into projects and activities.

A project is a meaningful objective with a defined end state. Activities are the repeatable actions within that project. Many activities must take place within a project to ensure its completion.

Let’s take the example of a sales project.

Although the outcome might be revenue growth, measuring revenue is a lagging indicator.

The activity that will drive the ultimate goal is the number of cold emails sent, cold calls made, follow-ups completed, and meetings booked.

These are the inputs that drive the outcome.

Once the work is framed this way, the next step becomes obvious: benchmarking.

You shouldn’t guess what ‘enough’ looks like.

You should study what the top (10%) performers do and what they actually execute. This will provide enough actionable data to know what’s working and what needs to change so you can hit your goals.

You can measure inputs using anything from apps, a spreadsheet, or pen and paper. Just make sure you are consistent and organized.

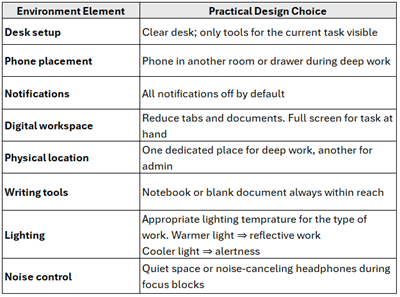

2) Environment Design: Win on Default Mode

Designing the right environment for work will remove the need to think or put effort into getting work done.

As humans, we will resort to doing the easiest and most entertaining thing available to us.

If distraction is easy, distraction will win.

Focus becomes easier when there is clarity about what to do and when there are no distractions.

Good environment design removes friction from the right behaviors and adds friction to the wrong ones.

A clear desk signals single-task focus.

A phone in another room eliminates temptation entirely.

Reducing the number of open tabs and documents reduces mental switching costs.

Table 2: Environmental design tips for better work

3) Habits and Rituals: Turn Intention into Default Behavior

“Follow effective action with quiet reflection. From the quiet reflection will come even more effective action.”

Habits and rituals exist to eliminate decision fatigue and ensure you enter ‘work mode’ seamlessly and consistently. You shouldn’t want to have to decide how to work each day. It should come naturally.

Plan in Advance: Weekly planning, done in advance, sets direction before urgency takes over. This is best done on weekends when there is nothing urgent, so you can plan the next week clearly and thoughtfully.

A brief night-before review and planning session reduces morning friction by removing uncertainty.

At the end of the workday, take the written brain dumps (thoughts and to-dos) from that day and organize them appropriately. It closes open loops by moving unfinished thoughts out of your head and onto paper. This clears mental residue and makes it easier to rest and reset.

Define the Anchor Task: Clarity before the day begins is important. The night before, define what truly matters tomorrow. Choose one anchor task (only one). This is the non-negotiable item that must get done for the day to count as successful.

The anchor task is usually the big, ugly, or boring thing you’re tempted to delay. The one that carries disproportionate impact. You can do other tasks during the day, but this is the priority around which everything else revolves.

Even if the day goes sideways, completing the anchor task ensures progress.

Start Small: A lot of the time, work feels heavy. The simplest way to defeat this is to break tasks into bite-sized pieces and apply the 2-minute rule.

Commit to starting for just two minutes.

Open the document. Write a sentence. Fill one cell.

Do something meaningful, even if small.

Starting creates an open loop that the mind wants to continue.

Keep The Goal In Mind: Having the long-term calendar with your vision and various duration objectives nearby helps. It keeps you grounded and focused on the long-term.

I also recommend printing your goal tracker if it's digital. That way, you can see the progress made without having to switch tabs. You can then update the digital progress tracker every night or week.

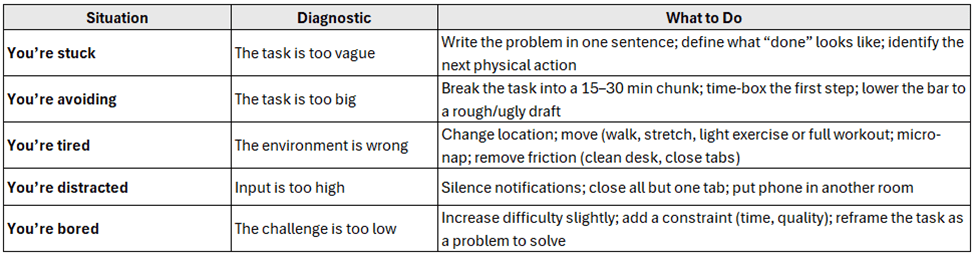

Stay Reminded of What to Do When Stuck: When people get stuck, they assume the problem is related to motivation or discipline.

The reality is that the brain is likely overwhelmed and conflicted about what to do or how to do it. My suggestion is to not push forward without understanding why you’re stuck. Instead of forcing progress, pause and diagnose the situation.

Ask yourself how you feel in the context of what it is you are supposed to be doing, because different problems require different responses.

The table below act as a decision aid when your brain resists work. It removes the guesswork (and creeping procrastination) and gives you a default response when you don’t know what to do or avoid the work.

Table 3: What to do when you resist work